To reduce the breeding mosquito population around your home and property, routinely check and dump all standing water and debris.

CHANGE IS THE NORM FOR BOTH COLOR AND SOUNDTRACKS

Field notes by Jeff Cantrell, photos courtesy of the MO Dept. Conservation

The month of April simply explodes with opportunities for nature viewing. The forest floor in a high-quality natural area will display a different setting of wildflowers every four or five days. The flora color palette will be heavy on the pinks, blues, and whites catering to specialized spring pollinators attracted to those colors and, sometimes, different fragrances. Only a few yellow and red native flowers this early season. The yellow flowers will likely dominate in the open country this summer and supply social insects and their kin with nectar in exchange for pollination services. These are mostly moisture loving flowers and they bloom while the forest canopy is tender with only tree buds and the youngest of leaves. Sunlight during this spring season streams in and warms the soil for these ephemeral bloomers and the shallow pools of waters. The pools benefit from the sunlight by staging a multitude of food webs in the water. The sunlit layer just below the surface has food chain “links” such phytoplankton and zooplankton increasing as fast as the flora color changes are happening just feet away on drier land.

I find these temporary pools fascinating because they are an ecosystem within an ecosystem, and they are very important to the ecological balance. Beyond the visual of the beautiful forest floor and the colorful migratory birds coming to the surface waters to drink, there are other attractions to these pools. This watery landscape has a spring soundtrack. Many frog and toad species are attracted to these temporary pools. The big puddles may dry up soon, but there is time for amphibian life cycles to progress and capitalize on the aquatic food webs already in place. Several species of amphibians (salamanders, toads & frogs) depend on these habitat features, and landowners may be interested in adding more for conservation purposes.

The soundtrack is commenced by the male frogs and toads calling for the arrival and mate attraction of the females. Some males rest their vocals and try to position themselves between a healthy calling male and an approaching female.

These males are referred to as “satellite” males by biologists, energy is important, and this is one way of not expending more.

The opening acts on this Ozark Forest soundtrack will most likely be spring peepers, western chorus frogs, gray tree frogs, American toads, and pickerel frogs. Southern leopard frogs have a “laughing” or chuckle sound to their calls and will be found at ephemeral pools at the forest edge and more open grassy areas.

Spring peepers are certainly a harbinger of spring, and their call is often one of the first sounds of spring nature lovers recognize. Naturalists listen for the peepers initially and know a few of the other species will follow in the weeks ahead. Frog calls revolve during the weeks of April and May similar to the progression of flowers with their timeframes to bloom and go to seed. Eventually the canopy of the forest fills in and the spring flora ceases under heavy shade. The young tadpoles quickly grow and transform to young adults before the water dries. Naturalists will now cast their observations to the open areas for more flowers of yellow, and listen for cricket frogs, green and bullfrogs on sunnier aquatic habitats.

Enjoy the music! The singers may be cold-blooded, but their vocals will make you smile! - Jeff

Jeff is a local Conservation Educator stationed at Shoal Creek Conservation Education Center, Joplin, MO Jeff.cantrell@mdc.mo.gov

Spring Peeper

Leopard Frog

Gray Tree Frog

Pickerel Frog

American Toad

sounds from Lang Elliott Music of Nature

Romps and Convocations are Going Strong in Missouri's Wilds

Field notes by J. Cantrell, photos courtesy of the MO Dept. of Conservation

Years ago, I was working an Eagle Day event at Schell Osage Conservation Area (near El Dorado Springs). These were extremely popular events with the public and school groups coming to view Omega or Phoenix, who were rehabbed eagles from the Dickerson Park Zoo, and to see wild eagles in their natural habitat. I staffed spotting scopes along the wetland and set up an area to let people view eagles perching in the treetops or on the lake’s icy surface. Unfortunately, eagles were firmly on the endangered species list then, and out of protected areas, in ideal habitat, they were rather rare for Missourians to see. Visitors eagerly lined up at the optics and I could tell by their facial expressions when they had a full view of our national symbol. They were thrilled at the view and slowly would step back and use their own binoculars to scan for other eagles on their own. The spotting scope outreach conservation event piqued interest and now they were open to learn a little about the habitat and the role the eagle plays in the environment. The observations of a kettling group of eagles riding the thermals in the midday sunshine are called a “soar” of eagles, and perhaps bringing the most interesting eagle behaviors is when they are grouped together on the ground either resting or feeding. A gathering of bald eagles like this is called a “convocation,” and it is thrilling. Educational steps in a simple form of exposure like this was one of the keys to bringing the bald eagle back from critically low numbers. Exposure may lead to a little understanding and, in turn, more understanding.

River Otters & their tracks

That same day at Schell Osage many of my audience members got to witness another comeback performance…river otters. We were fortunate enough to have a mother otter and four teenager otter pups come through the waterways behind the groups of people waiting for their turn at the scopes. On snow-covered land or frozen over lakes, otters travel by alternating running and sliding. Otters swimming together have an uncanny resemblance to sea life mammals; they surface often at unpredictable places. They may bob up or even come ashore briefly to get a better look at their surroundings and “touch base” with otter siblings. They are amusing to watch, thus a group or family of otters on the move are called a “romp” due to their playful nature. Rarely do we catch them resting together, but if so – their grouping is referred to as a “raft.” Historically, otter numbers were decimated by unmanaged harvesting, habitat destruction, and water pollution. That day years ago was when I witnessed people’s excitement and celebration of otter success as well. Since then, over the last 25-30 years river otters have steadily, slowly increased and filled their habitat niches. The otter is an extraordinary animal to learn about and discover in the wild. Over the past year, I’ve had nine different accounts of people visiting with me and sharing photos and videos of otters. Surprisingly their stories were very similar to the Schell Osage account …a group of otters traveling, playing, and even sliding together. Otters are one of the most intelligent mammals in North America and a naturalist observing them will quickly pick up on their body language and verbal communication skills. Predators are vital to a healthy ecosystem and the river otter is an efficient predator of freshwater clams, crawdads, and certain stream fish.

February is a wonderful time to easily view bald eagles in the wild and to happen upon otter signs along the rivers and wetlands. I hope to catch you out in the wilds this month and enjoy the conservation successes of these comeback species! - Jeff

Cheers to 2022!

Wishing you a happy New Year! May it be filled with new adventures and good fortunes.

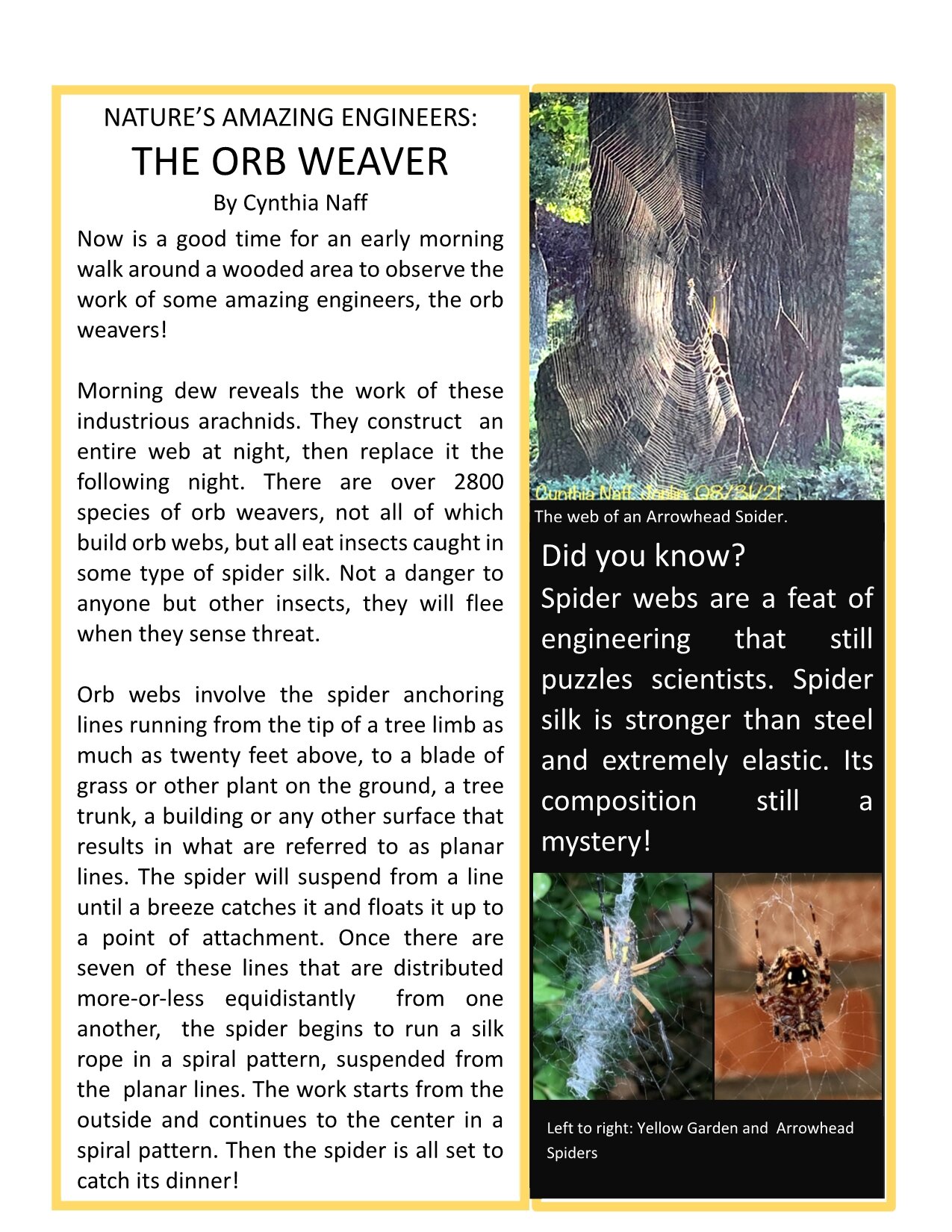

Orb Weavers

Earth And Arbor Day 2021

Meet The Cicada By Kelly Hock

Not all people are bug people, but I have found that sometimes a little information can go a long way toward stemming fear, so let me introduce you to the harmless and annual Scissor-Grinder Cicada.

The Scissor -Grinder Cicadas are the bulging-eyed, shell-leaving creatures that crawl out of the ground and buzz around like giant, hyper, intoxicated bugs on a mission, quickly flying into things during the dog days of summer here in Missouri. Cicadas are often seen being devoured by ants on a sidewalk or being chased and swatted at by cats and dogs like a new play toy, until they become a treat.

Named for their song sounding like scissors being sharpened on an old-time grinding wheel, the Scissor Grinder Cicada in Missouri, Neotibicen pruinosus, is an "annual" cicada. Their life cycle begins with the females laying eggs in small branches on trees and woody plants. Once they hatch, the nymphs drop to the ground and burrow down to reach a root, suck sap, and grow and molt several times. Eventually, they use their feet designed for digging and clinging to make their way back up to the surface. From there the fully developed nymphs take an epic journey to find a place to exit and leave their shell. You can find tiny ½ inch holes in the ground around trees where you see their shells or exuviae. Once a spot has been selected, the cicada begins its transformation by pushing out its head, then thorax, elegantly leaning backward and bending upside down like Cirque Du Solei contortionists. At the last moment they are hanging so far out that it appears they will assuredly fall to their doom. Then the cicadas gracefully and extremely slowly reach forward, grabbing the head of the shell from which they are emerging, and gently release the rest of their body. The cicadas hang on to the heads of their exuviae; bodies stretched out, their wings slowly unfolding in such silent, minuscule amounts it is almost imperceptible. Once their wings are entirely revealed, they go through their final steps of transformation. The cicada goes through unsuspected and beautiful hues of gold on the way; their bodies and wings change colors and harden, becoming the adult Scissor-Grinder. These are reminiscent to what we have come to see all these summers. Once a fully transformed adult, the scissor grinder only lives 4-5 weeks.

The scissor -grinding buzz we hear is the mating call of the male, who emerges first. He makes his call, which can individually be as loud as a lawnmower, by expanding and contracting his tymbal near the wings on the sides of his abdomen. The female, who emerges a few days later, responds by clicking its wings together to alert males to her location. She will only mate once, so she may not accept her first suitor. You can imitate the female’s clicking response by snapping your fingers at a slow yet steady pace but be aware; it calls a male cicada which might land on you. (If interested, one can easily watch video examples with a quick internet search) After mating, the female begins her hunt for the perfect sized branch of a quarter to half an inch diameter, to hide her eggs. She will make several tiny slits and lay her eggs 20-40 at a time, laying a total of 200-400 eggs. Once fully transformed from a nymph, the adult scissor-grinders only live 4-5 weeks.

Ten Myths, Facts, & Benefits of Cicadas

1. Cicadas are not locusts. Locusts are the things of biblical plagues, a type of grasshopper devouring plants and leaves. Cicadas suck the sap and are incapable of chewing and devouring anything. Cicadas aren’t primarily beneficial.

2. Cicadas do not attack anything and do not bite. Not only do they not bite, they cannot bite. They don't have chewing/chomping mouthparts. They are designed to suck sap and could not bite you if they wanted to. If they fly into you, I promise it was not an intentional attack. Everything seems to eat these bugs, and it just desires evasion; sometimes it isn't very good at it.

3. Pretty much everything that can eat a cicada eats cicadas. That includes people around the world. Cicadas have as much protein as red meat. They contain all nine amino acids, making them a complete protein and an excellent source of antioxidants.

4. Although saplings or small woody plants made up of primarily small branches can suffer irreparable damage due to the females' egg-laying, Cicadas do not harm adult established trees. Cicada nymphs feed on the sap in the roots, which takes some of the nutrients, but this has not been known to damage trees. Cicadas can also benefit established trees by aerating the ground, pruning the small branches, and their dead bodies give nitrogen back to the soil.

5. Most all other insects that leave an exuvia, eat it. Cicadas don't because they don't have the mouthparts.

6. The exuviae of cicadas have been used in traditional medicines throughout history for ailments such as migraines, inflammation, cancer, convulsions, and more, but WARNING it is known to be dangerous for pregnant women.

7. You can tell females and males apart by their abdomen. The females' abdomens come to a pronounced dark point, and males are more domed: think “shield bug”.

8. There are over 3,000 types of cicadas—Periodicals that emerge in 7,13, and 17-year intervals and Annuals, which is a misnomer, that emerge every 2-5 years with overlapping generations.

9. All cicadas have the same life cycle. They only vary in how long they stay underground. Some ponder if the 13 and 17-year cicadas may emerge during prime years to avoid predators' cycles and avoid becoming prey for other animals.

10. The fluctuating seasons are believed to be affecting the emergence time of some cicadas as some broods are emerging early.

*Photos courtesy of Kelly Hock and MDC

Water is a Cherished Resource

Water is an extraordinary and multipurpose topic. It is vital for human health, economics and the systems of the environment.

The Naturalist Bystander, Let the Baby Be!

It is extremely rare for a wild mother to abandon her healthy young. If babies are found in the wild place where they belong,

Master Naturalists out for a stroll

The only way to enjoy a prairie is to stroll through it while paying close attention to everything it has to offer.